Results of testing the telescope on the Earth's atmosphere

The search for life on exoplanets is entering a phase of intensive research. The LIFE space telescope promises to be a breakthrough in this field. Unlike the James Webb Multipurpose Space Telescope (JWST), designed to perform a variety of tasks, LIFE will focus exclusively on searching for biosignatures on exoplanets.

LIFE — This is an interferometer consisting of five separate telescopes operating in a coordinated mode, allowing the telescope to be larger and its resolution to be improved. By observing in the mid-infrared, LIFE will be able to detect spectral lines of important bioindicators such as ozone, methane and nitrous oxide. The plan is to place the telescope at the L2 Lagrange point, which is 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, the same location as JWST.

Although LIFE is still just a concept, researchers have taken steps to test its effectiveness. Since the telescope itself has not yet been built or launched, scientists used data from the Earth's atmosphere to conduct testing. Earth was treated as an exoplanet, and LIFE methods were tested on real data of the Earth's atmosphere under various conditions. A tool called LIFEsim was used to analyze the data. This study differs from the usual practice of using simulated data to test mission capabilities — in this case actual data were used.

In practice, the Earth as an exoplanet would be a barely visible point. LIFE will only be able to observe the spectrum of the atmosphere, which will change over time, depending on the duration of the observations. This led the researchers to question how observing geometry and seasonal changes would affect the results.

Researchers have a lot of observational data about the Earth available to them to work with. They analyzed three different observing geometries: two polar and one equatorial. We used data on the state of the atmosphere in January and July, which are characterized by the largest seasonal fluctuations.

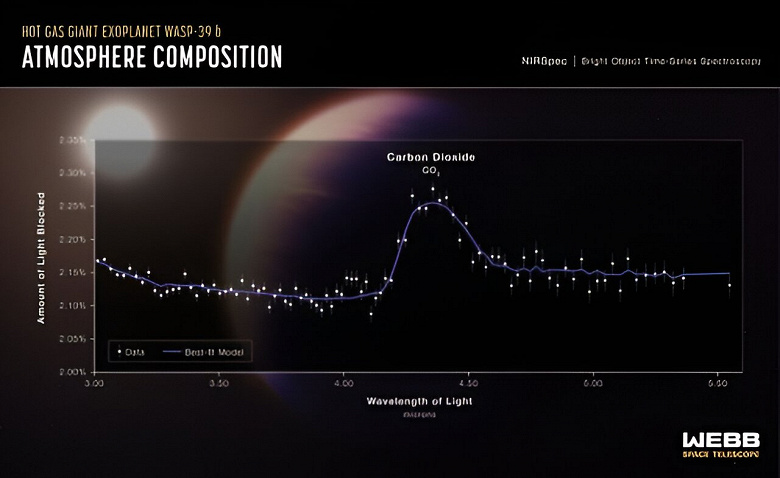

Among the many complex configurations of planetary atmospheres, researchers have focused on chemical signatures such as nitrous oxide, chloromethane and bromomethane that can be produced by living organisms. Also of particular interest are carbon dioxide, water, ozone and methane, which are key biological signatures on Earth and may indicate the possibility of life on other planets.

LIFE successfully detected carbon dioxide, water, ozone and methane on Earth. Traces of liquid water were also found on the surface. It is noteworthy that the results of LIFE observations do not depend on the observation angle relative to the Earth. This is important because the angles of future LIFE observations are unknown.

Seasonal variations are more difficult to observe, but it turns out that this will not complicate future missions. They could help estimate the potential habitability of nearby exoplanets, despite difficulties in interpreting the data due to seasonal changes in atmospheres.

To better understand the time required for LIFE observations, the researchers developed a list of targets. Planets with radii from 0.5 to 1.5 Earth radii were selected, located around M and FGK stars at distances up to 20 parsecs from the Solar System, which can be detected by LIFE. These goals were determined based on previous studies. The results indicate that some planets will require only a few days of observation, while others may require up to 100 days.

Scientists have identified «golden goals» — exoplanets that are most easily observed. An example of such targets are the planets in the Proxima Centauri system. Monitoring them will only take a few days. However, for more complex cases, such as Earth's twin exoplanets located about 5 parsecs from Earth, LIFE will require about 50-100 days of observations to detect biosignatures.

At the moment, the LIFE space telescope remains only a potential mission. This is not the first proposed mission dedicated to studying signs of habitability of exoplanets. In 2023, NASA proposed the creation of a Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO) with the goal of imaging at least 25 potentially habitable exoplanets and then probing their atmospheres for biosignatures. However, the study authors believe that LIFE is the best option for achieving these goals.