The Milky Way's supermassive black hole sends gamma rays toward Earth every 76 minutes

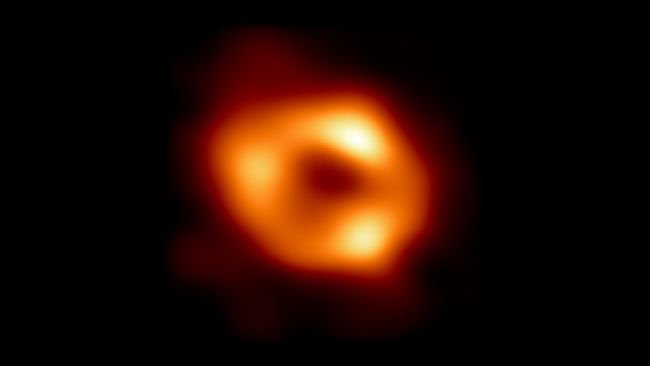

A study conducted by astrophysicists at the National University of Mexico found that gamma rays from the vicinity of the black hole Sgr A* at the center of the Milky Way are associated with a clump of gas spinning at high speed. These results may help solve a mystery that has long puzzled astronomers.

Initially, gamma-ray bursts from Sgr A* were noticed in 2021. It was obvious to experts that this radiation could not come from the black hole itself, since the event horizon, which is the boundary for all black holes, does not allow anything, not even light, to leave it. The researchers concluded that the radiation must originate in the environment surrounding the black hole.

Supermassive black holes are known to emit bright radiation from their surroundings when their gravitational influence disrupts conditions in the surrounding gas and dust, creating an accretion disk. As they feed on this surrounding material, black holes emit energy across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, including gamma rays.

However, this did not explain the gamma radiation from Sgr A*, since the Milky Way's black hole is surrounded by a very small amount of matter and “feeds” extremely slowly. To put this into perspective, this is equivalent to a person eating one grain of rice every million years.

Using data from the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope collected from June to December 2022, astrophysicists conducted a study to figure out the source of the gamma rays. They identified a pattern in gamma rays that appeared near Sgr A* every 76.32 minutes. This emission period is half as long as the period between X-ray pulses, also observed in the vicinity of the black hole. This suggests that these two radiations are related to each other.

The discovery, called the “oscillatory physics mechanism”, suggests that both X-rays and gamma rays are emitted by a clump of gas orbiting Sgr A* at about 30% of the speed of light, or about 320 million kilometers per hour. Astrophysicists suggest that it is this rapidly rotating gas that emits light at different wavelengths, with periodic flashes.

This discovery could shed light on the environment of supermassive black holes, especially when they are not as active as Sgr A*, located at the very center of the Milky Way.